On the other side of disaffiliation, traditionalist congregations pursue prayer, revival, and revitalization.

June Fulton felt weird sitting in the third pew.

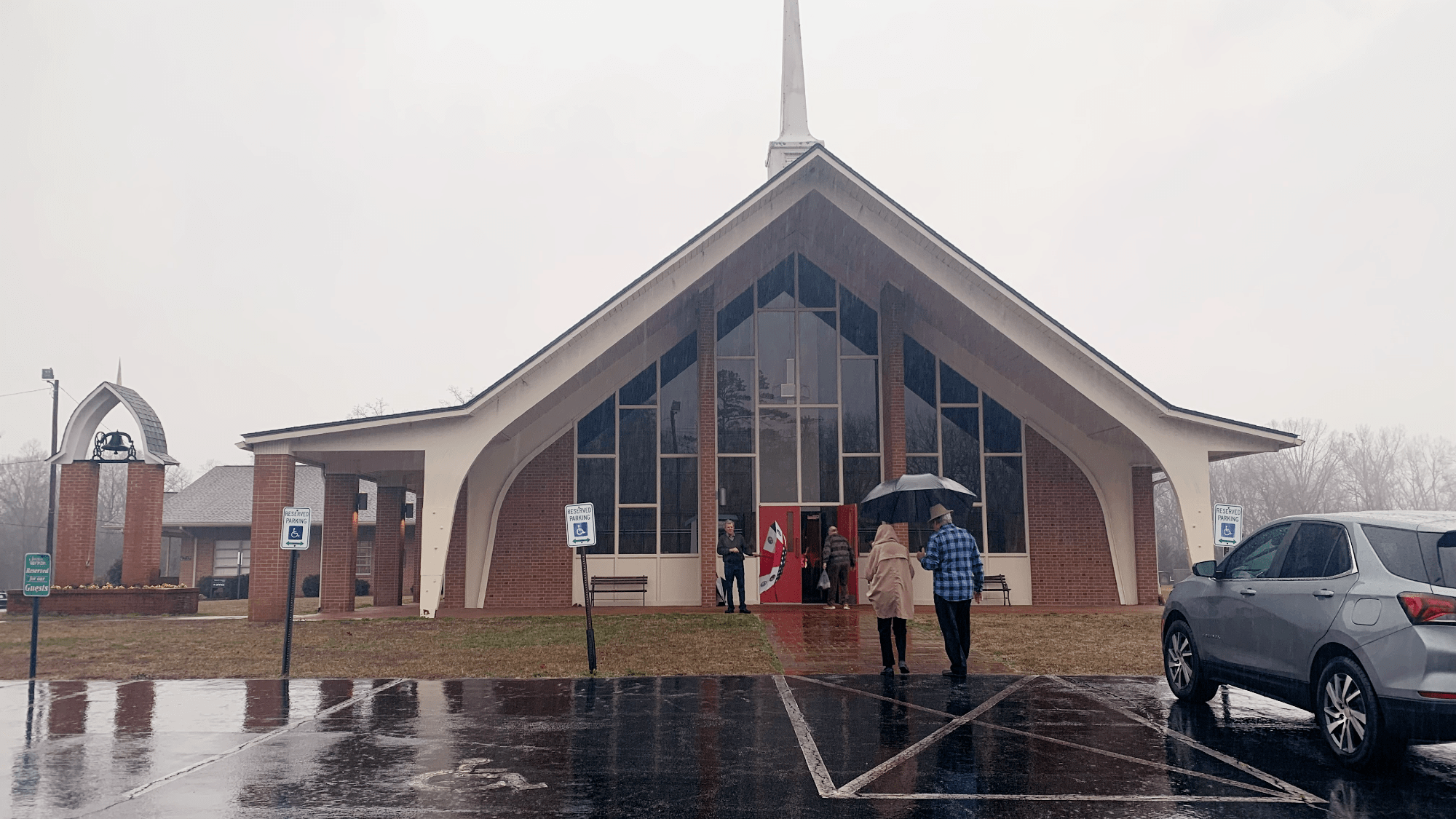

At every service since she joined the choir when she was 12 years old—her whole life, basically—she has sat with them on the stage behind the pulpit at Mt. Vernon United Methodist Church (UMC), in Trinity, North Carolina.

But there was no singing at the disaffiliation vote. So Fulton, now one of the matriarchs at Mt. Vernon, took a spot in the pew next to a friend.

“Everybody filled out their piece of paper, a ballot, and they had to sign it,” Fulton told CT. “Every person went up and put their paper in the basket and then we sat there quietly. So quietly. It was so strange to sit there so quietly as we waited.”

Representatives from the denomination collected the ballots. They went into a back room and counted the votes to see whether the small rural church would be one of the thousands to exit the UMC over LGBTQ affirmation, fidelity to traditional Christian teachings on sexuality, the authority of the Book of Discipline, and years of bruising ecclesial conflict.

Fulton leaned over to her friend and said how sad it all was. She said this was not something you ever wanted to do.

Her friend said, “I just wonder what it’s going to be like. I think we’ve made the right decision. But I just wonder what it’s going to be like,” Fulton recalled.

Fulton wondered that too. She hoped the congregation would soon put it all behind them—the debates; the acrimony and the weight of it; the sorrow; and the endless, complex process of disaffiliation.

“We can go forward,” she said, “and go back to doing the things we always did do: caring for people, looking after people, and being the church.”

Mt. Vernon …